[dropcap type=”circle”]G[/dropcap]olf returns to the Olympics this year in Rio after a 112 year period out of bounds – though sadly several of the world’s top players have decided not to bother.

To understand the game’s exile and controversial comeback it’s necessary to explore its bizarre beginnings.

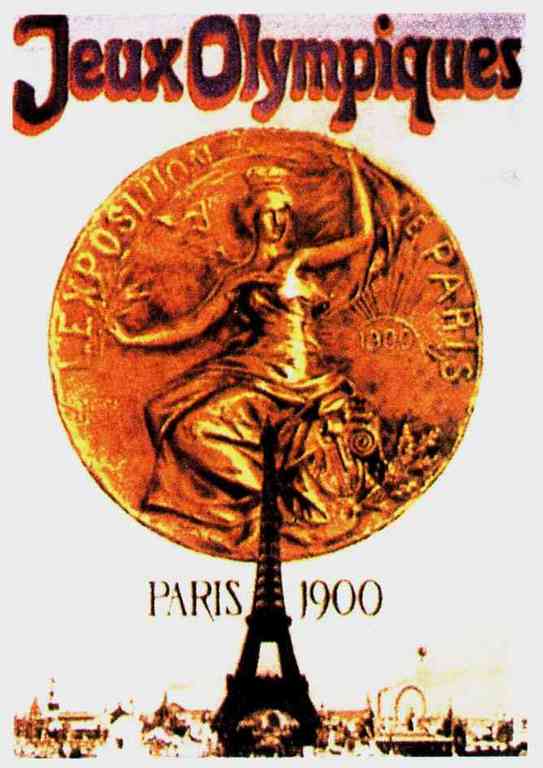

On October 2 1900, four years after the first modern Olympic Games, twelve men played 36 holes at the Compiegne Golf Club north of Paris.

Only a few of them seemed to have been remotely aware that they were competing in the first Olympic golf tournament. Back then the Games were mere adjuncts of the World’s Fairs and poorly organised to boot, so ignorance was probably inevitable.

What is certain, though, is that American Charles Sands, of the St. Andrews Golf Club in Yonkers, won the first Olympic gold medal for golf with rounds of 82 and 85. He pipped Walter Rutherford of Jedburgh in Scotland by one shot.

The next day, the ladies event, played over 9 holes, was won by another American, Margaret Abbott of the Chicago Golf Club. Her round of 47 proved too good for the rest of the field – which included her mother, who finished seventh

Charles Sands was full of self belief. He competed for the first American Amateur Championship in 1895 having taken up the game of golf just three months earlier. But hubris can be cruel. Sands came up against his nemesis Charles Blair MacDonald and was thrashed 12/11. He never played in the U.S. Amateur again – and even his Olympic triumph was destined to be but a footnote in the history of the sport.

Margaret Abbott was in France studying art when she and her mother sought diversion by entering what they thought was the ladies championship of Paris. It is doubtful that this misunderstanding was their fault – a contemporary historian remarked of the Games’ organisers, the Paris Exposition Company, that “their intelligent appreciation of the task before them remains yet to be disclosed.” Confusion abounded and helped seal Margaret Abbott’s victory; she told friends that the main reason she won the competition was “because all the French girls misunderstood the nature of the game scheduled for that day and turned up in high heels and tight skirts.” Happily she became the first American woman to win an Olympic event; sadly she went to her grave without knowing it.

No mighty oak would grow from this farcical acorn, but Olympic golf achieved some sort of credibility in the United States in 1904. Albert Lambert of St. Louis, Missouri, had taken part in the 1900 golf tournament while on a business trip to Paris, so when the Olympic circus was scheduled to visit his hometown he discussed the opportunity with his father-in-law, George McGrew, founder of St Louis’ Glen Echo Golf Club.

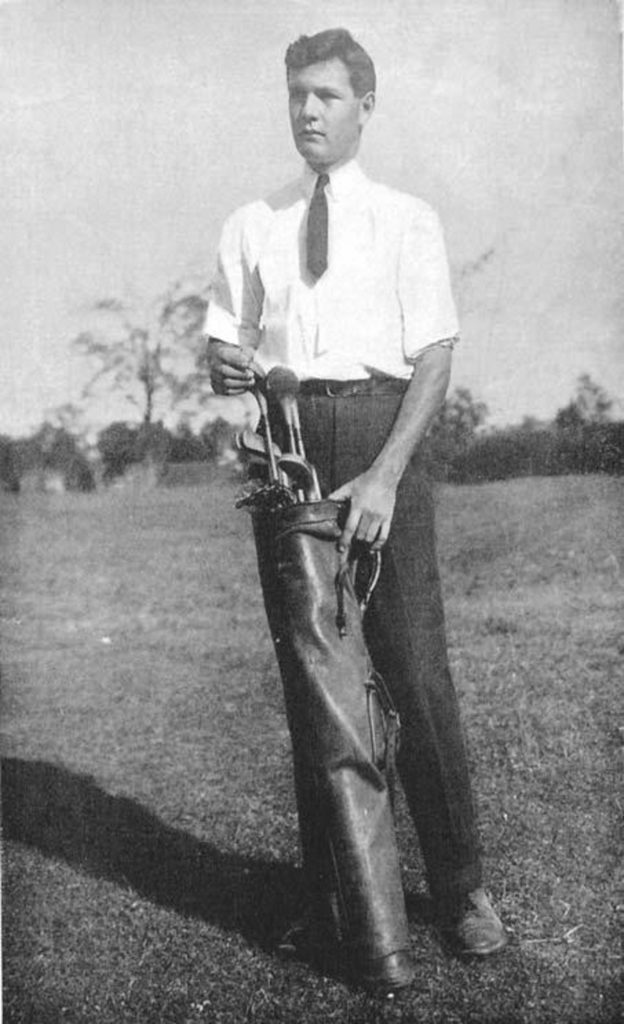

The rest is history, albeit not very well known. More than seventy Americans and three Canadians arrived at Glen Echo to go for golfing gold, and on September 19 the players teed off for the match play qualifying. Only one of the Canadians made it through, namely George Lyon of the Lambton Golf and Country Club in Toronto.

Lyon was a gifted but unusual sportsman who first picked up a golf club at the age of 38. In previous years he had proved successful in baseball, tennis and cricket. In 1876 he also found the time to become Canada’s champion pole vaulter. In 1904 he was forty-six and his unorthodox swing – which apparently owed more to a slog into cow corner than the tempo and symmetry of an Adam Scott – was criticised for being that of a ‘coal heaver’.

Nevertheless George Lyon heaved his clubs and himself into the final and a match against the youthful American H. Chandler Egan. Egan had been recently crowned U.S. Amateur champion and was the hot favourite. Furthermore, his playing style and his proper demeanour – Lyon was prone to tell jokes and do hand stands during a round – found favour with purists.

The day of the final dawned cold and wet and the combatants fought the rain as hard as they fought each other. By all accounts it was a gruelling contest and Lyon emerged the victor by 3 and 2. His body, honed, toned and toughened by all that baseball, cricket, pole vaulting and coal heaving, endured the cruelty of the elements better than that of young Egan who, after the medal ceremony, promptly retired to his bed while Lyon dressed for dinner.

And so it came to pass that the still reigning Olympic golf champion is a Canadian, George Lyon – a champion who will not be toppled until later this year when golf returns to the Olympics after an absence of more than a century.

Mind you, there should have been golf when Britain hosted the Olympics in 1908. Here in “golf mad Blighty” there was an expectation that we could organise a second to none tournament. Plans were ambitious and excitement was intense – there was to be a 108-hole stroke play event at three courses: Royal St. George’s and Prince’s GC, both in Sandwich, and Cinqueports GC in nearby Deal. Lyon, the defending champion, would joust with formidable British amateurs including Robert Maxwell and Hoylake’s John Ball and Harold Hilton.

But within the description “golf mad Blighty” there is one key word. Mad. The importance attached to Olympic golf by the Royal and Ancient Golf Club in 1908 can be judged by their response to a letter sent by the organisers of the Games. The R&A didn’t reply. A subsequent very British row about eligibility meant that, in the end, no one entered and George Lyon stepped off the boat from Canada to find that he was the only competitor. When offered a symbolic gold medal for his pains he respectfully declined it. His disappointment can only have been tempered by the fact that the Olympic golf crown still rested upon his head – though he could not have imagined that it would do so for so long.

It is hardly a surprise that after these false starts Olympic golf was disqualified. After the British debacle a century would pass before a campaign, launched by the International Golf Federation at Royal Birkdale in 2008, would aim to give the game its proper place in the Olympic global spotlight. The following year the International Olympic Committee voted by 63 to 27 for golf to be part of the Brazil Summer Games of 2016. At the time Jack Nicklaus said: “I think it’s fantastic, an unbelievable day for the game of golf. The impact is going to be felt all over the world, which is what I’ve always felt about the game. The game is a mature game in many countries, but it never had the opportunity to grow in many others. People of all walks of life will be inspired to play the game of golf, and play for sports’ highest recognition. For all sports, that has been a gold medal.”

Golf needs the Olympics. The Games unite a global sporting audience and sow seeds of sporting inspiration across the world. Countless people who have never picked up a golf club will follow the fortunes of their countrymen and women and be tempted to learn the game. In Brazil alone, where the population numbers more than 200 million and yet there are only 100 or so golf courses, there is a fabulous opportunity for golf to grow and flourish.

So let us thank and salute those early competitors of more than a century ago. Some may have had precious little idea what was going on; one may even have sailed across the Atlantic to discover no one wanted to play him. But they are a reminder of one of the glories of golf: that anyone, on his or her day, can be a champion.