[dropcap type=”circle”]L[/dropcap]etters sent home to Scotland in 1915 and 1916 by the great uncle of a Heswall man are a terrifying reminder of the horrors of trench warfare.

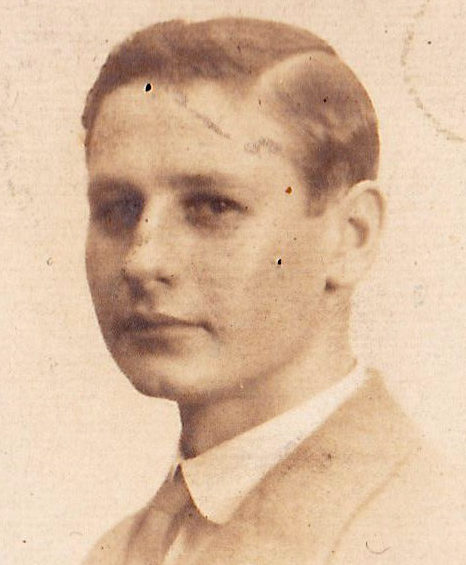

David Tindal was 26 when he was killed by shellfire in France’s Somme valley on June 30th 1916, the day before the huge offensive that caused unparalleled slaughter on both sides.

The battle raged until November 18th and left both sides heavily depleted. On the first day alone 58,000 British troops were put out of action and one third of these were killed. When it was over British and French casualties numbered 485,000 to the Germans’ 630,000. A German officer wrote: “Somme. The whole history of the world cannot contain a more ghastly word.”

David’s great nephew is Alasdair Coates, a retired headteacher and Scot who has lived in Heswall for 40 years. He told Heswall Today, “David was a qualified solicitor who enlisted to join his fellow countrymen serving in the trenches. He was a favourite with my grandmother who remembered him fondly and often spoke of him, and my great-grandfather, a doctor in Glasgow. His letters are touching, honest and beautifully written, especially when you consider the circumstances under which some of them were composed.”

Although David was behind the lines when he died he had already endured the terror of German artillery barrages aimed at the firing line and would have joined the so-called Big Push had he lived.

When his soldiering career began David was optimistic but also realistic. On November 22nd 1915 he wrote to his father: “We have now got our marching orders and ere [before] you read this I shall have set forth on the greatest adventure of my life. You will not, I hope, worry on my account as I believe that fate will be kind to me, but should the cards go against me in this great gamble, I trust you will remember that it has always been my most earnest desire that I should meet death suddenly and painlessly.”

Six months later, having seen at first hand the consequences of endless shelling including dreadful mental and physical damage, his mood had changed dramatically. “You people at home are often told, ‘there is nothing of importance of report.’ Men are being killed all along the long line with unfailing regularity…Peace is the thing about which everyone here dreams – though I doubt if we shall ever see it. We have our confirmed optimist here who has invited me to his house in Arran after the war…the chances are he will never see Arran again.”

As he and his pals trained for the Somme offensive David described their preparations in a letter to his sister Catherine on June 21st: “We were in a very fine bit of country the other day practising manoeuvres for a special purpose. The whole division was out – it was a great sight – everything complete, to the cavalry massed in the rear in readiness, and the aircraft signalling overhead. And now I ought to tell you that there may not be many more letters – at least for the next few weeks, but I shall send postcards whenever possible. Keep your eye on the papers and the map.”

Two days later he wrote to his father: “And now I have no time for any more except to beg you not on any account to be anxious on my behalf. You may be sure I shall not run unnecessary risks…Above all, do not grieve for me if I should chance to be knocked out…You may be sure that I shall write again whenever possible, and I think I can promise you that the letter will be interesting.”

This was to be David Tindal’s final letter home.

David Tindal’s letters have been used as the basis of an award-winning short film which imagines what his war would have looked like had he used a smartphone to record it rather than pencil, paper and postcard.

The film, called tWWItter, brings the events of a hundred years ago vividly into the 21st century.