[dropcap type=”circle”]S[/dropcap]tar Trek is 50 years old today, the perfect excuse to travel back in time to 1950 when the genius of two men turned the seaside town of Southport into the centre of the universe and created a hero who pushed back the final frontier well before James Kirk. This is the story of how and why.

It was a time of contrasts. On the one hand World War II was fresh in people’s minds and austerity was the order of the day; on the other was the excitement and promised prosperity of the space and atomic ages.

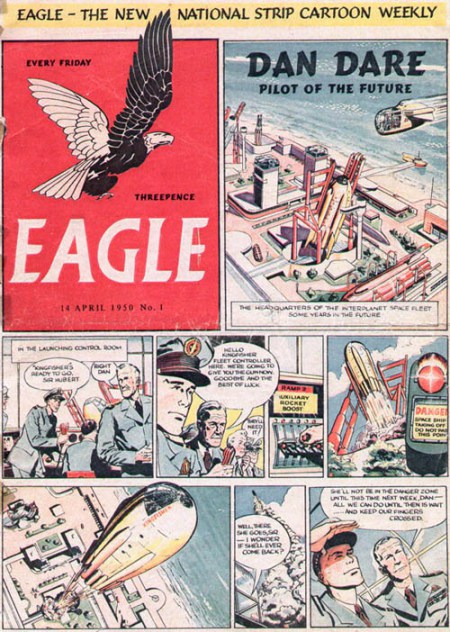

Into this world, in April 1950, came a dream of things to come; a revolutionary comic called Eagle that introduced us to the Pilot of the Future.

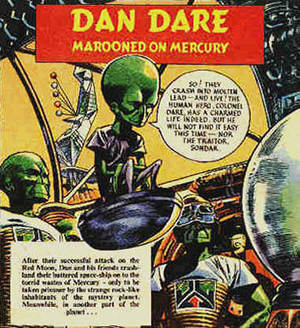

He was the distilled essence of the British fighter ace – courageous, quick thinking, honourable, a knight of the skies – and his name was Daniel McGregor Dare.

A modest man, he would have been embarrassed by his celebrity; because, when Eagle rolled off the presses, he became an overnight sensation, a national institution, and the timeless star of what is, to some, the world’s greatest comic strip.

Astonishingly, Eagle was the brainchild of a vicar and an unknown artist. The Reverend Marcus Morris presided over the church of St. James in Birkdale; while Frank Hampson was a recent graduate from Southport School of Art.

Morris, then a father of three young daughters, had been appalled by the influx into Britain of American horror and crime comics. Already the publisher of a parish magazine called the Anvil that had attracted nationwide attention, he resolved to fight back. Hampson, who had contributed drawings to the Anvil, was an obvious collaborator; and thus the seeds of a great creative partnership were sown.

Morris’ concept was to create a comic that was intelligent, literate, optimistic, and imbued with a moral code. At one point in Eagle’s development the lead strip was to feature a flying padre, an airborne solution to all manner of ethical dilemmas. But finally a science fiction story was settled on, one which gave Frank Hampson free imaginative rein and the opportunity to reveal his prodigious talent.

The two men put together a dummy issue that included Dan Dare on the cover and, inside, the life stories of saints and other uplifting tales of derring-do, together with illustrated pages that explored science and technology. Marcus Morris toured London publishers, but to little effect. Almost at the point of giving up he pitched his idea to Hulton Press, the company behind the famous Picture Post. Hulton bit and sent Morris a telegram which read: DEFINITELY INTERESTED. DO NOT APPROACH ANY OTHER PUBLISHER.

The Eagle was about to land.

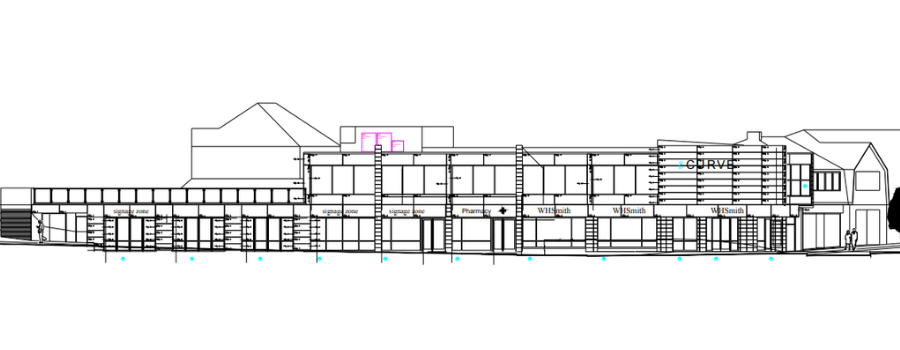

Two things were needed: a studio and a team of artists to work in it. The first was easily solved by an old bake house in the Churchtown district of Southport; the second by urgent recruitment.

Artist Greta Tomlinson was one of the first to sign up: “It was very basic, a flagstone floor and a tin roof; there was cold running water in the corner. It was freezing cold in the winter and boiling hot in the summer…I had answered an advert for a comic strip artist and thought I’d give it a go. So I went for an interview and saw the bake house, saw Frank’s work on the board and just thought it was fantastic! Just wonderful! And I felt, I’ve just got to have this job.”

The work that so impressed Greta brought something new to the comic strip form. Frank Hampson strove for a high level of realism – he often drew from life using family members and his fellow artists as suitably dressed models. His technique suggested a feature film on paper: he cut dramatically from scene to scene, using angles and light to suggest mood and emotion, and he created panoramic establishing shots that lured the reader into a strange but credible future whether on earth or distant planets.

Wisely, Eagle also hired expert consultants, among them Sir Arthur C. Clarke, then a young aspiring science fiction writer: “In 1950, of course, the idea of space travel was not as crazy as it had seemed to most people a decade earlier. Because, towards the end of the war, two things had happened: the V2 rockets and, above all, the atomic bomb – these two things made people realise that there would be a future very different from the past.” In fact, Frank Hampson had first hand experience of the V2; towards the end of the war, while serving in Belgium, he saw one lift off and begin its ballistic journey towards London.

Queen guitarist and astronomer, Brian May, was an early fan: “When we were at school and it was raining we were allowed to stay in and you had cupboards all around and out would come the comics…and there used to be Eagle comics amongst them, and I remember thinking, ‘these are incredible, these are like real photographs of real things happening in space.’”

But in many households, Eagle still had to overcome prejudice against comics. Monty Python member and film director, Terry Jones, lived in one such home: “I remember Eagle being launched and my brother went and bought a copy…and my mother hid it in a drawer because she said, ‘You mustn’t tell your father you’ve got a comic in the house!’ And then she had to speak to my father and tell him that the editor of the Eagle is a clergyman, so it should be all right.”

Eagle soared, selling around 750,000 copies a week and generating an enormous range of merchandise: toothpaste, pyjamas, toy ray guns, slideshow projectors and countless other spin-offs. Dan Dare was the Star Wars of his day. There was even a radio version of his adventures that crackled through the airwaves from Radio Luxembourg.

Interviewed in 1978, Frank Hampson observed: “Dan Dare came at a time of great shortages after a long and exhausting war. Everything was very bare, everything was utility, everything was right down to rock bottom. So the fantasy of it had a great appeal, the colour of it, too; and generally it expressed the ideals of the time based on the United Nations organisation.”

Brian May, who owes his enthusiasm for astronomy to Dan Dare, could not get enough of the space faring adventurer: “I remember getting to the end of a page and it suddenly went ‘con’ – well, it nearly always said ‘continued’, but this time it didn’t. And my dad said to me, ‘it says concluded.’ And I said, ‘what does that mean?’ And he said, ‘the end.’ And I went, ‘NOOOOO!’ – because I hadn’t realised a new story would start next week.”

The other strips and cutaway drawings of steam turbines and aircraft carriers were fine in their own way and as beautifully drawn and inked as everything else in Eagle. But it was Dan who drove its success. His struggle with Venusian despot, the Mekon, the green and big-brained leader of the soulless Treens, was a corker of a story which, in its own way, had plenty to say about good and evil, right and wrong, and the limits of resistance. Dan Dare had a good mind and a good heart; he had a ray gun too, but he preferred not to use it. He was a hero for a new world, one which, sadly, did not last.

Eagle’s success endured for a decade. But then, with the comic under new ownership, Hampson’s studio, now in Epsom, was scaled back and he was ordered to shorten and simplify his long, complex stories. He was also asked to write for characters he had not invented and in which he did not believe. So Hampson chose instead to quit and his departure, combined with the advent of the sixties and changing attitudes to Eagle’s tone, began its decline. Dan Dare was removed from the front cover and, in 1967, his final mission ended on the inside pages.

This compounded another huge disappointment. Hampson and Morris had signed contracts which, while paying them well, had sold the copyright to Eagle and Dan Dare: Pilot of the Future. Dan Dare merchandise had made fortunes, but not theirs. This was a source of bitterness that would trouble Hampson for the rest of his life.

But at least the priceless legacy of Eagle and Dan Dare remains for all to share. It is arguably the case that modern British science fiction owes a great debt to a character who, more than six decades ago, made it acceptable for everyone to imagine the impossible and ask the question, what if?

The comics world also remembers The Pilot of the Future, and artists across the globe recognise the skill and pioneering achievement of Frank Hampson, once voted il prestigio maestro by the Italian comics industry.

Terry Jones hopes that Hampson will not be forgotten. “I think one of the tragedies of Frank Hampson is that he was so under rated. People did not celebrate him as this great genius that I’m absolutely convinced he was.”

Equally certain is that, thanks to Hampson and The Reverend Marcus Morris, Eagle has its place in history as an artistic, editorial and commercial triumph that, back in 1950, put Lancashire on the interstellar map.