[dropcap type=”circle”]I[/dropcap]n 1854 two United States naval officers share a cabin on a ship called the USS Cumberland. Their names are Raphael Semmes and John Winslow and we can assume they are friends as well as colleagues.

When they write their autobiographies years later, neither man will mention the time they spent together.

Semmes and Winslow were destined to find themselves on opposite sides in the American Civil War, skippering vessels which fought one of the most famous battles in maritime history. A battle which ended a truly remarkable story of courage or villainy, brilliant naval warfare or piracy, call it what you will.

The victors were Winslow and the USS Kearsarge. The vanquished were Semmes and the Confederacy’s most destructive commerce raider, a ship which had terrorised Union shipping for two years. A ship built in secret. A ship half crewed by Englishmen from Liverpool. A ship called…

ALABAMA.

In June 1861 the American Civil War was just weeks into what would be a bloody four year conflict. Nevertheless, a quick thinking Confederate secret agent arrived in Liverpool and commissioned the building of a vessel known only as Number 290. Both he, Georgian James Bulloch, and Birkenhead shipyard owner, John Laird, knew the score. The anonymous craft must purport to be a merchant boat – after all, isn’t Great Britain neutral? The two men shook hands on the deal and construction began.

Union interest was quickly aroused. The US consul, Thomas Dudley, made repeated complaints to the British authorities that Number 290’s intentions were far from peaceful. He employed spies and private investigators to infiltrate the Laird work force but still, thanks to incompetence or deceit, the Government refused to act.

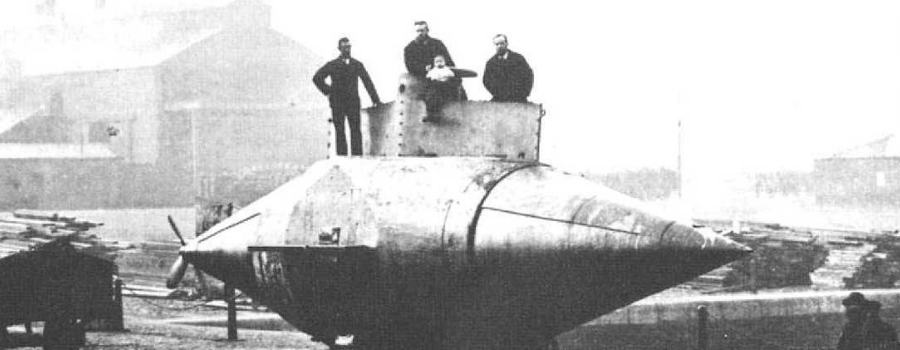

Number 290 was launched on May 14 1862, and christened Enrica by a mysterious, unnamed woman, probably Bulloch’s wife. As Union pressure continued to mount, Bulloch maintained his illusion by hiring an English skipper and crew. Time was running out – rumour had it, correctly, that the United States War Ship Tuscarora was steaming to the River Mersey intent on stopping Enrica leaving port.

Sea trials were hastily arranged and the Enrica, complete with her local skeleton crew, left British waters and set course for Praya Bay in the Azores. Bulloch, meanwhile, traveled to London, bought another boat and loaded her with coal, guns and ammunition. This vessel then set the same course as the Enrica.

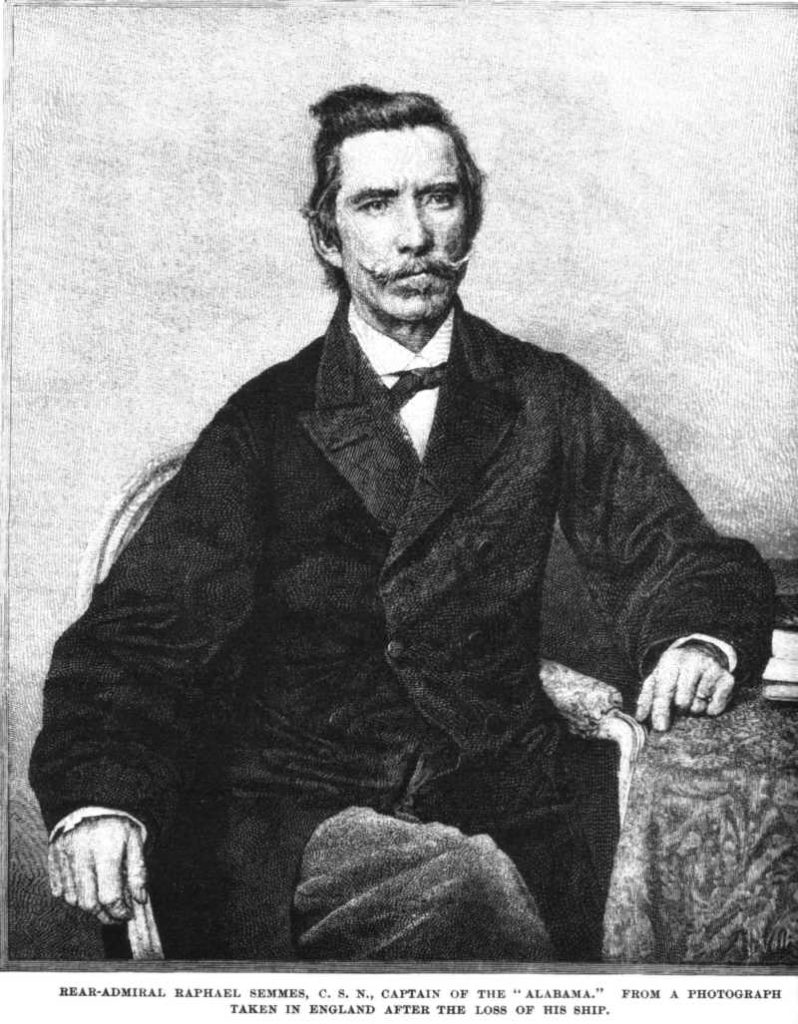

Back in Liverpool, Confederate naval officers were gathering in secret, awaiting the arrival in the Mersey of the steamship Bahama, also crewed by Britons. On board was Captain Raphael Semmes, who collected them and headed for the rendezvous in Praya Bay.

On August 20 the Bahama met up with the other two vessels. Guns and equipment were transferred and, in less than 72 hours, the Enrica became a fighting ship.

Semmes gathered together the crews of the three ships and explained that Enrica was now a Confederate warship and that she would be deployed as a commerce raider against Union shipping. He gave the men a choice – either ship out on the Bahama, or sign on with him. If they stayed they could expect double pay, double rations of grog and plenty of action, plus a share of any prize money from captured ships. They could also, he added, expect tough discipline.

Almost to a man, they chose to stay.

On August 24, the British flag was lowered and replaced by the Confederate banner.

The Alabama was born.

For the next twenty months the CSS Alabama roamed the seas to act out one of the greatest sagas in naval history. Newspapers the world over carried stories of her exploits. The US and British governments exchanged repeated diplomatic blows as her tally of victories increased.

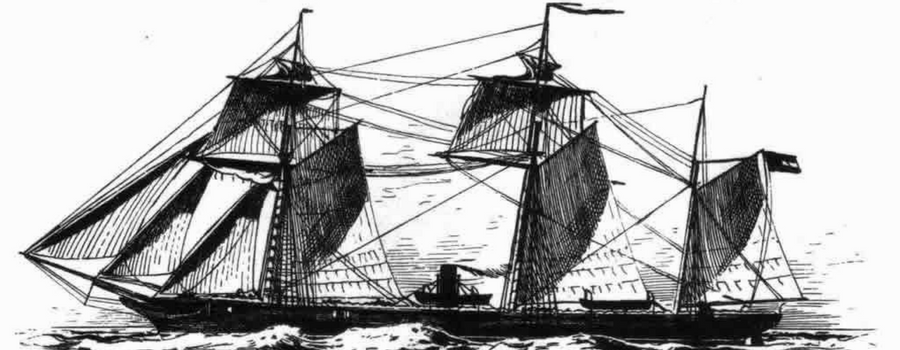

There was nothing new about commerce raiding, but the ferocity with which the Alabama set about her task was staggering. Raphael Semmes knew the Alabama was fast enough to catch the swiftest clipper and run from the North’s battle ships if she had to. Armed with six 32 pounder cannons and two pivot guns, and with the advantage of both steam and sail, she was a commerce raider second to none.

In early October 1862, steaming west towards New York, the Alabama was pounded by a cyclone for over an hour. Suddenly all was calm – she was now at the very centre of the storm. The men on board knew that only one ship in a thousand survived such an event.

The Alabama was such a ship. When the cyclone passed over her, lashing her for a second time, she was still sailing.

Captain Semmes went into port only when absolutely necessary; he took supplies from captured ships. The Alabama was rarely out of action, destroying more than fifty Union ships, releasing ten on bond, and turning another over to Confederate use. The total cost to the Union was almost five million dollars in lost vessels and cargoes.

But inevitably the campaign took its toll and the Alabama needed repairs. Captain Semmes decided to make a run for the neutral French port of Cherbourg. Arriving there on June 11 1864 he released prisoners taken from the ship’s latest victims and asked for permission to enter dry dock. He was told that only the Emperor, who was relaxing in Biarritz, could make such a decision.

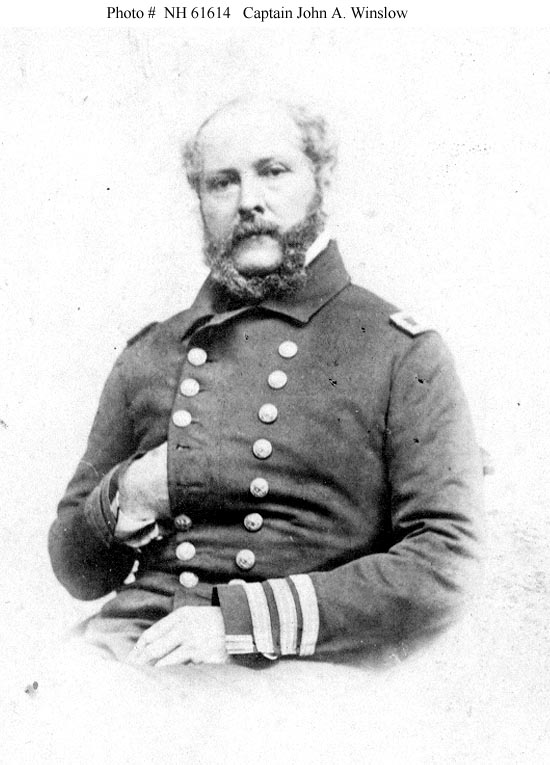

So, as the Alabama waited for Napoleon III to complete his holiday, news of her arrival in Cherbourg reached Flushing in Holland where the United States War Ship Kearsarge was standing by. Captained by Raphael Semmes’ former shipmate, John Winslow, the Kearsarge set sail with all speed.

When the Kearsarge steamed towards Cherbourg harbor, Winslow could see the Alabama still waiting for dry dock. She was in a pretty poor state, but Winslow knew he couldn’t attack her in French waters. So he turned the Kearsarge around and took up station outside the breakwater. He would simply sit and wait until the Alabama left port.

Captain Semmes was now faced with a simple choice. He could stay safely on neutral territory and let the Alabama die slowly. Or come out fighting.

Semmes didn’t hesitate. A note was delivered to the Kearsarge via the United States Consul in Cherbourg. Semmes stated politely but bluntly that, as soon as the Alabama was re-coaled, battle would commence. As the Alabama was prepared for battle the predominantly English crew amused themselves with this song:

“We’re homeward bound; we’re homeward bound

and soon shall stand on English ground.

But ere that English land we see

We first must fight the Kearsargee.”

Word spread. A crowd that would finally number more than 15,000 began to gather in Cherbourg. Every vantage point along the coast was taken by people eager to watch the greatest raider of all time fight for her life. Excursion trains from Paris carried thousands from the capital. Artists set up their easels overlooking the harbour to record the battle for posterity; even the great Edouard Manet would later capture this defining moment on canvas.

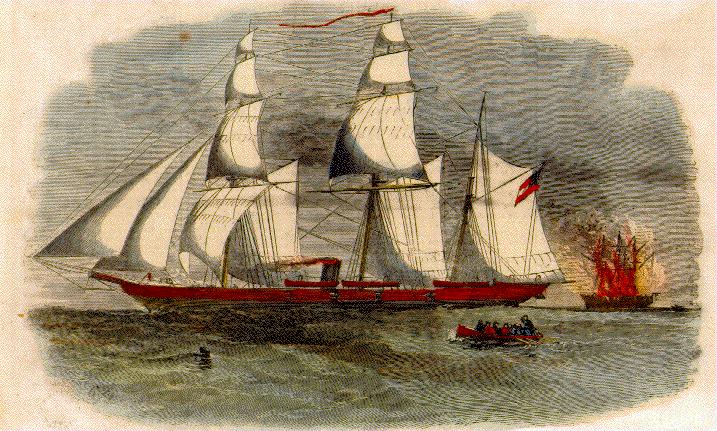

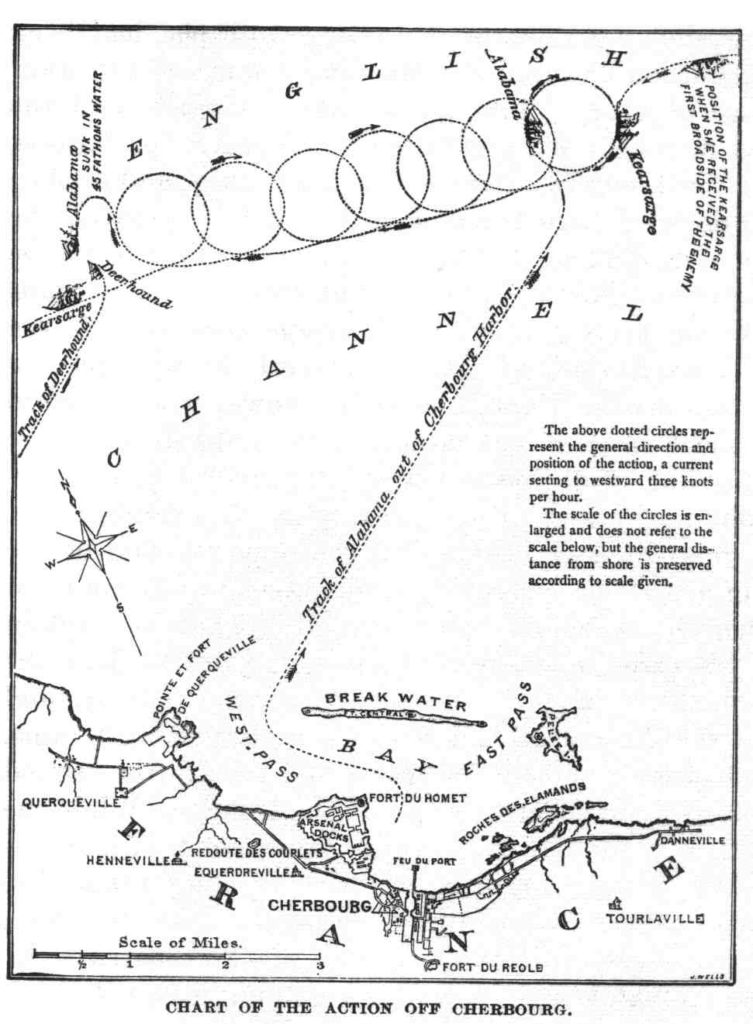

At 9.30 in the morning of Sunday June 19, a day of fine weather and low winds, the CSS Alabama steamed out of Cherbourg harbor. The USS Kearsarge was standing off some seven miles out.

As the two ships closed on each other, the Alabama opened fire. The Kearsarge replied as the two ships circled each other.

But the Alabama had problems. Her powder was in poor condition after so long at sea. Some of her shells hit the Kearsarge but failed to explode. And she was taking more and more punishment. What is more, Winslow had covered the hull of the Kearsarge with chains, a primitive form of armour, and spectators also observed that the firing of the Alabama’s gunners was often wild and ill-considered, while that from the Kearsarge was cool and calculated.

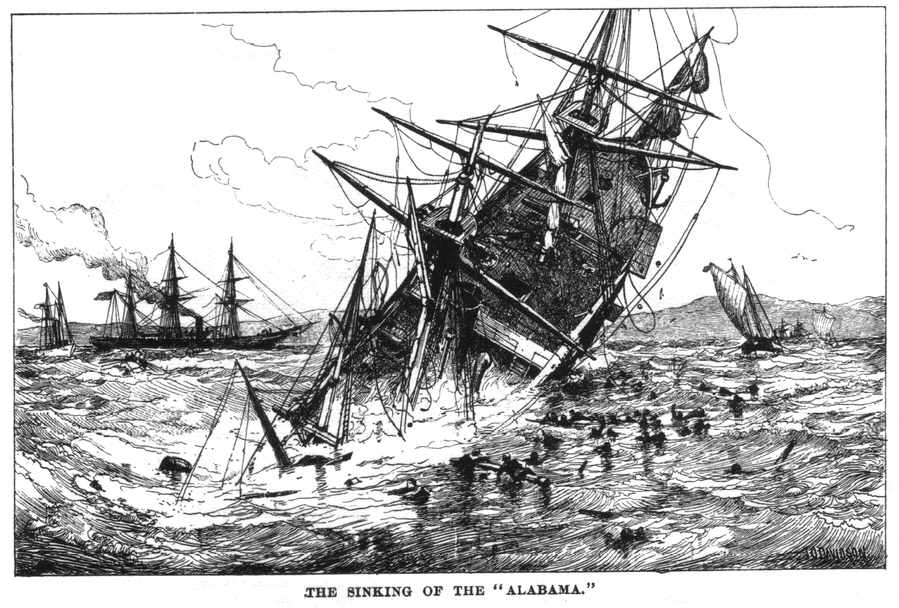

Hit in the stern below the water line, her engines disabled, the Alabama began to sink. She carried on firing until Semmes gave the order to abandon ship.

As the Alabama flooded there was no cheering from the men on board the Kearsarge. All was silence as the Alabama went down.

Small boats picked up the survivors, including Captain Semmes, who was taken on board a steam yacht owned by a John Lancaster of Hindley Hall in Wigan. Remarkably, Hall had come to Cherbourg to take a ring side seat at the battle. He took Semmes to Southampton and safety.

21 members of the Alabama’s crew were killed, 12 by drowning. 21 were wounded and 70 made prisoners of war. The Kearsarge suffered only three wounded, one of whom died later from his wounds.

An historic lawsuit ends the Alabama story. In 1871, the British government agreed to pay more than fifteen million dollars to the United States, admitting that it had failed ‘to use due diligence in the performance of its neutral obligations’.